Power to the (Women) Farmers

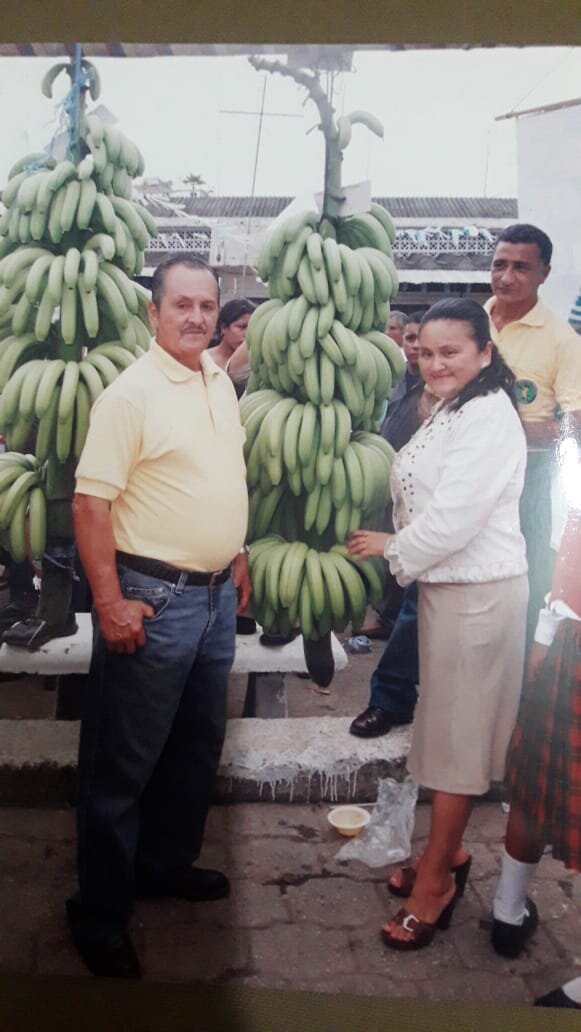

Cecilia representing AsoGuabo as board member at a local school and Fairtrade premium funding recipient.

In the fair trade world, farmers form the backbone of the supply chain and are essential partners for the businesses with whom they work. However, in discussions about farming, well-intentioned speakers on the receiving end of the supply chain tend to fit farmers into boxes, conjuring an image of “The Farmer” as a middle-aged (and in the U.S., white) male. This stereotype becomes a powerful representative for a diverse group, which actually includes all genders, ages, and races. Perpetuating the stereotype of the male farmer not only leads to generalizations, but also prevents the experiences of others from being shared and accepted.

The stereotype of farmers as men does not mean that women are less likely to do farmwork. Women have long participated in farming activities, and the FAO estimates that 43% of farmers globally are women (likely more, due to underreporting). However, a 2019 survey of U.S. farmers showed that women are less likely to call themselves farmers than men are, as they may take on tasks less associated with fieldwork, such as animal care, family management, and quality control. Professor Monica M. White attributes this tendency of gendering the farmer with capital ownership — white men are often the owners and operators of capital (farmland) to which other groups have been denied access. Those denied groups’ responsibilities, though essential to the successful operation of a family farm, are distanced from the farm and the capital it represents. Even women participating in fieldwork shied away from calling themselves farmers: women surveyed in the northeastern U.S. reported falling into the role of “farmer’s wife,” a descriptor they adopt even when doing field work and making important decisions about the farm.

Even less is published on the experience of women in banana-producing countries, especially from the perspectives of the women farmers, themselves. The Equal Exchange banana team recently spoke with banana farmer Cecilia Manzanillas, of AsoGuabo cooperative in Ecuador, to hear her experiences and perspectives on farming and the key role that women farmers play.

Photos, left to right: Cecilia Manzanillas stands with her family on her banana farm; Cecilia and her father present bananas grown on their farm; Cecilia poses outside the headquarters of farmer co-op AsoGuabo.

Having grown up in a farming family in Ecuador, Cecilia took over one hectare from her father in 2004, and became a member of the Asociación de Pequeños Productores El Guabo (AsoGuabo). She used her degree in business administration to run a successful farm business, and took on leadership roles on the Board of Directors of both AsoGuabo and the parish of Tenguel. Noting the care and mentorship from others along the way, Cecilia highlighted the importance of her family, who consistently supported and respected her personal decisions. Her father not only shared his knowledge about farming, business, and land stewardship, but also encouraged her to pursue what she was passionate about.

Cecilia noted that in Tenguel, women’s roles have changed over time:

“[Before] the man would be involved in working in the field and running the actual agriculture, and women would have been in the house, or either doing the shopping, or watching kids, or doing the cooking. So now, that’s not the case anymore, women are also involved in fieldwork and agriculture directly. ”

Women are not only involved in fieldwork; they also take on roles in the community of Tenguel. In its early days, AsoGuabo had a female farmer as its president who paved the way for more female banana farmers to join as members of the co-op. Now, 40% of members of most community organizations in Tenguel are women, and five women serve on AsoGuabo’s Board of Directors. Tenguel’s inclusive community, which women have been shaping and reshaping over the years, has fostered the growth of a women’s collective. The collective extends opportunities to entrepreneurial women, while organizations like AsoGuabo invest time and resources in the professional development of their female members. Cecilia’s passion for accessibility and community development even led her to take an AsoGuabo-sponsored trip to the Dominican Republic, to meet members of CONACADO cooperative and exchange ideas about programming and women’s leadership.

Women, farming, and empowerment

Cecilia’s advocacy for individual support and investment is not unfamiliar, but is rarely echoed in literature about women and farming. As I have left the farming world for a job in an office, and as I have researched this piece, it has been intriguing to hear armchair agriculturalists’ perspectives on what life is like for farmers, and women farmers in particular. How do they know what farmers need? Whose perspectives have informed what they say? And how, without hearing everyone’s perspective, have nonfarmers decided that it is their job to empower women in farming? Cecilia’s voice, and the voices of all farmers, are essential for dispelling myths and generalizations that tend to be propagated by those with less experience, who have the privilege of speaking on their behalf.

While fair trade as a movement works to build solidarity with producers and artisans, the power dynamics inherent in development and empowerment continue to call for a critical look at whose voices are heard. While landownership and gender roles present barriers to women farmers, talking about women as less empowered in some contexts risks taking away some of the power that they have on the ground, power that may not fit into the global North’s boxes. Women hold essential roles on family farms through the skills they have acquired, and have used these skills to claim local leadership roles. Agriculture continues to evolve, and these skills have often propelled women to develop entrepreneurial innovations for their farms as economies of tourism and “boutique” agriculture gain prominence.

Cecilia brought the issue to the foreground, pointing to inclusivity and investment in individuals as a foundation for equitable farms, organizations, and communities. Noting that historically, women in her area had been reluctant to take on leadership roles in her parish, she highlighted how the inclusive nature of her co-op was a platform for her to both invest in herself and use her leadership skills to give back to the community. As a leader, she sees not only the growth of her crops as a priority, but also the growth of people in her community:

“Women, but also people in general, need to grow, that’s something that’s very important for oneself, you need to be able to learn and then to teach what you’ve learned, and have that be a constant exchange. And taking steps forward is something that’s a very beautiful thing, and going from being a producer to being part of a Board of Directors, and having people validate you as someone who has taken that step of growth is something that makes you feel very big.”

Refusing to acknowledge gender as a barrier to her own career, Cecilia emphasized that when families and communities invest in and support individuals, those individuals will both flourish and continue the cycle by giving back to the communities who supported them.

Discussing fair trade, Cecilia reframed power dynamics at play, noting that the weekly income offered by fair trade partnerships was an opportunity for her to operate her farm more sustainably. Cecilia and members of her co-op saw the opportunity inherent in the fair trade model, and took that opportunity to market a premium product, and in turn invest in their communities. She emphasized how women can become agents of change:

“Women are valuable, we are intuitive, we are entrepreneurs, we are economists. We don’t need to study the economy to be economists, we are financial in every aspect of what we do in our lives.”

Through innovation and engagement, in bananas, agriculture, and beyond, women are an essential part of the Equal Exchange supply chain, and are innovators of the future of food.

References

Brasier, K. J., C. E. Sachs, N. E. Kiernan, A. Trauger, and M. E. Barbercheck. 2014. Capturing the multiple and shifting identities of farm women in the Northeastern United States. Rural Sociology 79 (3):283–309. doi:10.1111/ruso.12040.

FAO. 2020. Women in Agriculture. United Nations. http://www.fao.org/reduce-rural-poverty/our-work/women-in-agriculture/en/

Frank, D. 2005. Bananeras: Women Transforming the Banana Unions of Latin America. Cambridge: South End Press.

Hochschild, A. R. 1989. The Second Shift. New York: Viking. Print.

Kimmel, M. 2011. The Gendered Society. 4th Ed. New York: Oxford University Press. Print.

Kurtiş, T., G. Adams, S. Estrada-Villalta. 2016. Decolonizing Empowerment: Implications for Sustainable Well-Being. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. DOI: 10.1111/asap.

Leslie, I. S., J. Wypler & M. M. Bell. 2019. Relational Agriculture: Gender, Sexuality, and Sustainability in U.S. Farming, Society & Natural Resources, 32:8, 853-874, DOI: 10.1080/08941920.2019.1610626

Rosenberg, G. N. 2016. A classroom in the barnyard: Reproducing heterosexuality in interwar American 4-H. In Queering the countryside: New frontiers in rural queer studies, ed. M. L. Gray, C. R. Johnson, and B. J. Gilley, 88–106. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Seuneke, P., and B. B. Bock. 2015. Exploring the roles of women in the development of multifunctional entrepreneurship on family farms: an entrepreneurial learning approach. Wageningen University. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.njas.2015.07.001

White, M. M. 2018. Freedom farmers: Agricultural resistance and the black freedom movement. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.